Author: Yuanxi Li yuanxili@uw.edu

Advisor: Dr. Rosalind Kichler rkichler@uw.edu

Introduction #

Cyberbullying, defined as aggressive or harmful behaviors occurring via the internet, social media, and mobile devices (Lee et al., 2015), remains prevalent even in emerging adulthood. This developmental stage (ages 18–25) is marked by significant life transitions, identity exploration, and increased social media use, exposing individuals to both positive and negative online interactions (Arnett, 2000). While cyberbullying research primarily focuses on adolescents, young adults, particularly LGBTQ+ individuals, remain highly vulnerable (Hinduja & Patchin, 2020). The shift of traditional bullying into online spaces disproportionately affects LGBTQ+ youth, leading to severe mental health consequences such as emotional distress, absenteeism, and substance use (Abreu & Kenny, 2017).

Among LGBTQ+ individuals, transgender individuals face particularly high rates of cyberbullying and associated mental health challenges, including increased risks of depression, anxiety, and suicidality (Su et al., 2016). However, despite growing concerns, research on cyberbullying in emerging adulthood remains limited, especially regarding transgender individuals. This study aims to address this gap by examining the extent and nature of cyberbullying experienced by transgender and non-binary young adults. By incorporating both quantitative and qualitative methods, this research seeks to enhance understanding of cyberbullying’s impact and inform strategies to create safer online environments.

Methods #

Data #

The data for this study were collected through an online survey designed to examine the extent and nature of cyberbullying experienced by transgender and nonbinary individuals in emerging adulthood. Participants were recruited through social media platforms such as Reddit, university LGBTQ+ groups, and other digital communities, using a snowball sampling strategy to increase participant reach. A raffle for a $50 gift card was offered as an incentive.

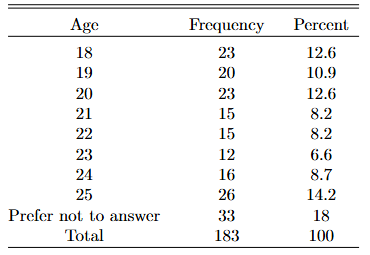

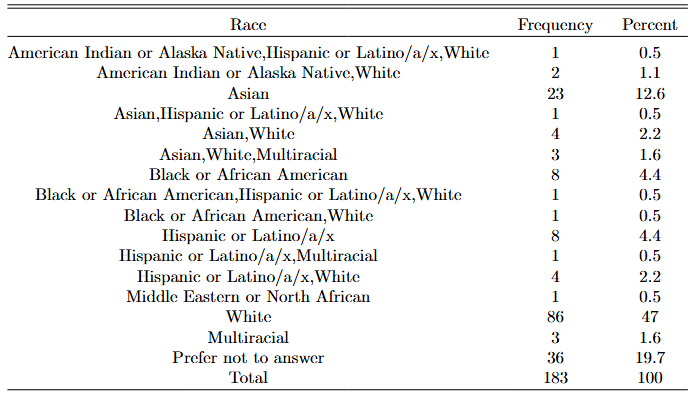

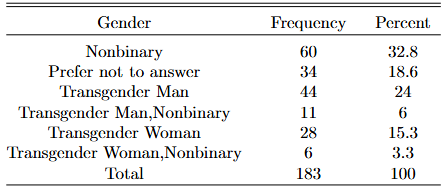

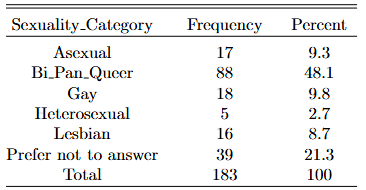

A total of 183 participants were targeted, with final inclusion criteria requiring respondents to complete all sections of the survey. Demographic variables such as age, race/ethnicity, gender identity, sexual orientation, and geographic location were recorded to assess their potential influence on cyberbullying experiences.

Measures #

The study utilized a mixed-methods approach, combining quantitative and qualitative data. The primary instrument was the Cyberbullying Victimization (CBV) Scale (Lee et al., 2015), which assessed the frequency and severity of cyberbullying incidents.

Cyberbullying was categorized into three types: #

- Verbal/Written Victimization

- Public online space: Insulting messages, threats, and rumor-spreading visible to a broad audience.

- Private online space: Harassment through direct messages, private group chats, or text messages.

- Visual/Sexual Victimization

- Public online space: Unauthorized sharing of private images/videos or public humiliation via sexual comments.

- Private online space: Non-consensual sharing of media and sexual harassment through private messages.

- Social Exclusion Victimization

- Public online space: Being blocked, removed, or intentionally excluded from online forums or community groups.

- Private online space: Exclusion from private group chats, direct messaging groups, or close-knit online communities. Each type of cyberbullying was measured using a five-point Likert scale: 1 = “Never,” 2 = “Once or twice,” 3 = “Once a month,” 4 = “Once a week,” 5 = “Multiple times a week.”

Social Media Use #

Participants were asked to indicate: Time spent on social media (less than 1 hour/day to more than 6 hours/day). Social media platforms used (Facebook, Instagram, Twitter/X, TikTok, Reddit, Discord, etc.).

Level of Outness #

Three questions measured participants' level of outness regarding their gender identity:

- Outness to extended family.

- Outness to friends.

- Outness to colleagues/classmates. Responses were recorded on a five-point scale ranging from “Not out to anyone” (1) to “Completely out” (5).

Demographic Questions #

Age, Race/Ethnicity, Gender Identity, Sexual Orientation.

Results #

Age Distribution #

Race/Ethnicity Distribution #

Gender Distribution #

Sexual Oririentation #

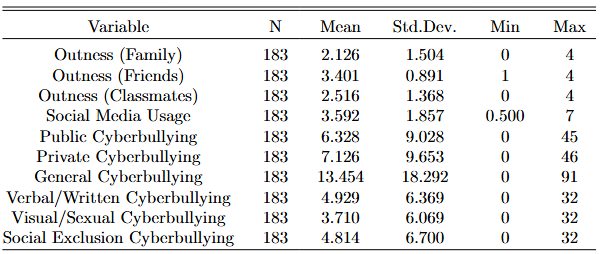

Descriptive Statistics #

- The study found that 78.1% of transgender and nonbinary participants experienced at least one form of cyberbullying. Among different types:

- Private cyberbullying (Mean = 7.13 incidents) was more frequent than public cyberbullying (Mean = 6.33 incidents).

- The most common form was verbal/written victimization (Mean = 4.93), followed by social exclusion (Mean = 4.81) and visual/sexual victimization (Mean = 3.71).

- Most Frequently Reported Cyberbullying Experiences

- Private Spaces:

- Having private messages shared without consent.

- Rumors spread in private spaces to damage reputation.

- Online harassment escalating into in-person harassment.

- Sexual rumors spread privately.

- Public Spaces:

- Being blocked in a public space to cause distress.

- Private Spaces:

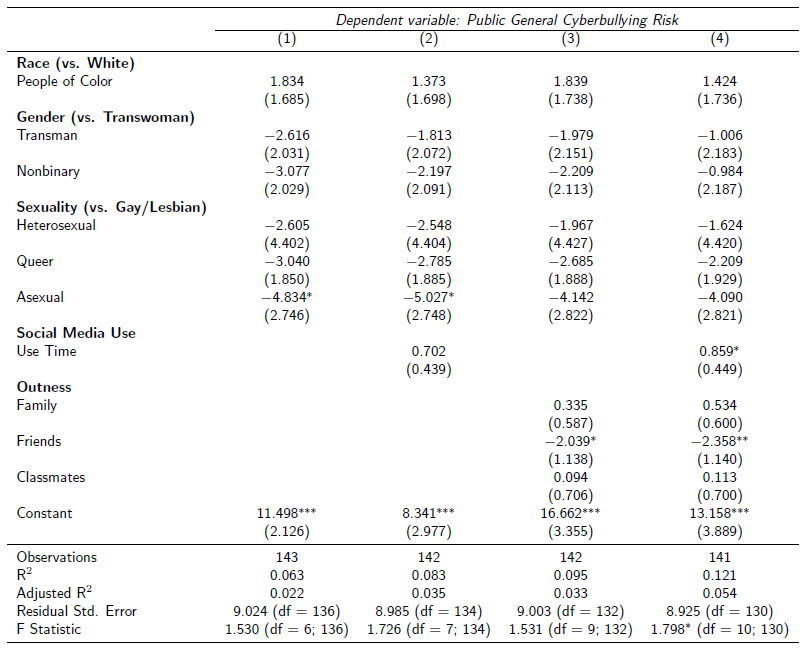

Regression Analysis of Public Cyberbullying Risk #

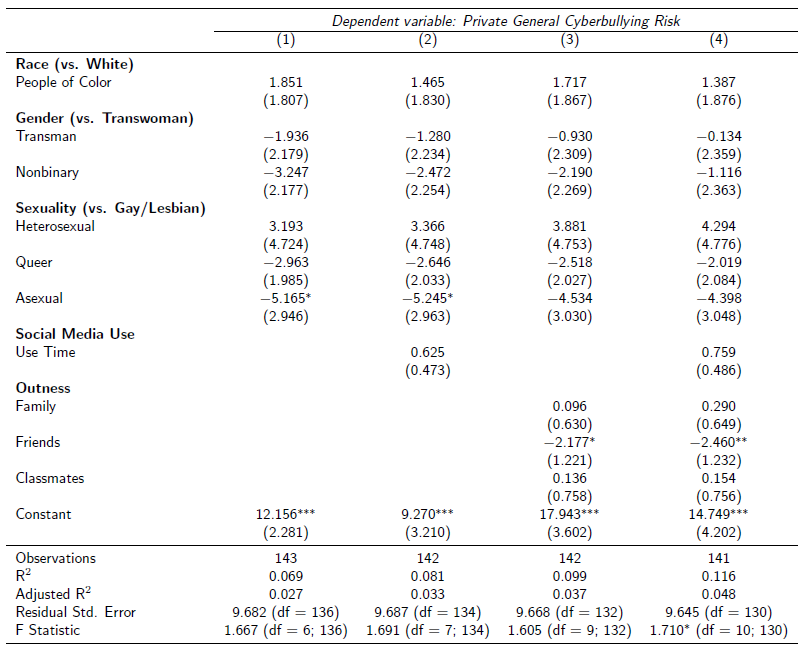

Regression Analysis of Private Cyberbullying Risk #

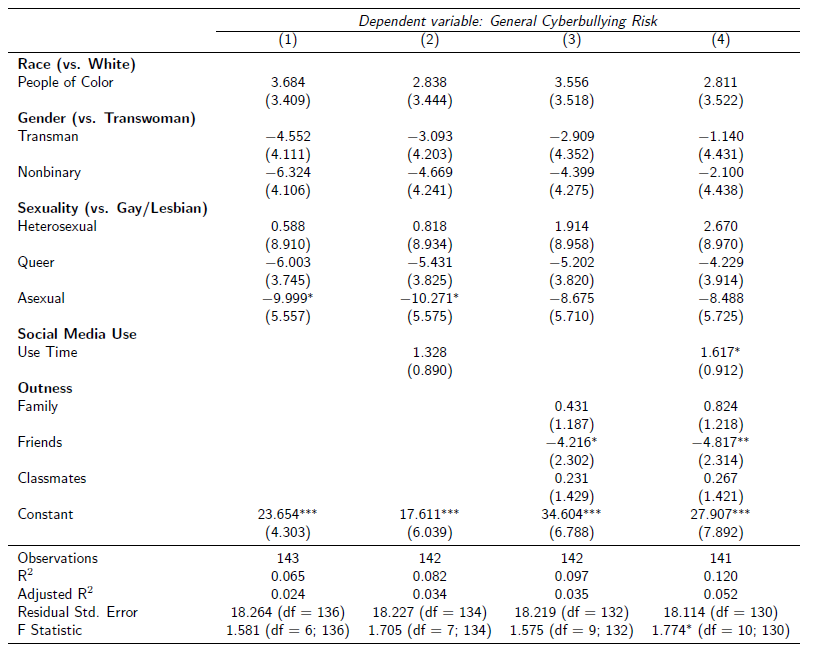

Regression Analysis of General Cyberbullying Risk #

- Social Media Usage & Cyberbullying

- Higher social media usage significantly increased cyberbullying risk (β = 1.617, p < 0.1).

- Outness to Friends as a Protective Factor

- Higher outness to friends correlated with lower cyberbullying victimization (β = -4.817, p < 0.05).

Open Ended Questions #

| Theme | Description |

|---|---|

| Harassment/Threats | General bullying, cyberattacks, online threats, cyberstalking. |

| Misgendering/Identity Exposure | Misgendering or forced outing of gender identity. |

| Rumor/Misinformation | Spreading false rumors about personal identity, relationships. |

| Privacy Violation/Doxing | Sharing personal or private information without consent. |

| Objectification/Fetishization | Sexualization, being targeted by chasers. |

| Erasure/Non-representation | Lack of inclusive options, feeling invisible. |

| Emotional Harm/Distress | Psychological pain, heartbreak, hurtful experiences. |

| Selective Disclosure/Trust Management | Strategic hiding of identity for protection. |

| Appearance-Based Bullying | Targeting based on physical looks or features. |

Discussion #

Cyberbullying Among Transgender and Nonbinary Individuals Through the Lens of Routine Activities Theory

Routine Activities Theory (RAT) posits that the convergence of three elements—motivated offenders, suitable targets, and the absence of capable guardianship—facilitates the occurrence of crimes, including cyberbullying. Applying this framework to our findings on cyberbullying victimization among transgender and nonbinary individuals offers valuable insights (Aizenkot, 2021, Navarro & Jasinski, 2011).

Motivated Offenders #

Transgender and nonbinary individuals often face heightened discrimination and prejudice, making them more susceptible to targeting by motivated offenders. The anonymity and reach of online platforms can embolden individuals to engage in cyberbullying without immediate repercussions.

Suitable Targets #

Our study indicates that a significant portion of participants are “out” to friends (Mean outness = 3.40), suggesting active engagement in social networks. This visibility, while fostering community and support, may inadvertently increase exposure to potential offenders. Additionally, the high prevalence of private cyberbullying incidents, such as unauthorized sharing of private messages, underscores the vulnerability associated with personal disclosures in online spaces.

Absence of Capable Guardianship #

The digital environment often lacks effective oversight mechanisms to prevent or address cyberbullying. The absence of real-time monitoring and the challenges in enforcing community guidelines contribute to an environment where cyberbullying can proliferate. Participants' substantial daily social media usage (Mean = 3.59 hours/day) further amplifies exposure risk in the absence of robust protective measures.

Implications for Prevention and Intervention #

Understanding cyberbullying through the RAT framework highlights the need for comprehensive strategies:

- Enhancing Guardianship: Implementing stronger moderation policies, AI-driven detection of abusive content, and accessible reporting mechanisms can deter potential offenders.

- Empowering Users: Educating transgender and nonbinary individuals about privacy settings, digital literacy, and self-protection strategies can reduce target suitability.

- Fostering Inclusive Communities: Promoting acceptance and understanding within online platforms can diminish the pool of motivated offenders by challenging discriminatory attitudes.

Reference #

- Lee, J., Abell, N., & Holmes, J. L. (2015). Validation of measures of cyberbullying perpetration and victimization in emerging adulthood. Research on Social Work Practice, 27(4), 456–467. https://doi.org/10.1177/10497315155785352.

- Arnett, J. J. (2000). Emerging adulthood: A theory of development from the late teens through the twenties. American Psychologist, 55(5), 469–480. https://doi.org/10.1037//0003-066x.55.5.469

- Hinduja, S., & Patchin, J. W. (2021). Bullying, cyberbullying, and LGBTQ students. https://ed.buffalo.edu/content/dam/ed/alberti/docs/Bullying-Cyberbullying-LGBTQ-Students.pdf

- Abreu, R. L., & Kenny, M. C. (2017). Cyberbullying and LGBTQ youth: A systematic literature review and recommendations for prevention and intervention. Journal of Child & Adolescent Trauma, 11(1), 81–97. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40653-017-0175-7

- Su, D., Irwin, J. A., Fisher, C., Ramos, A., Kelley, M., Mendoza, D. a. R., & Coleman, J. D. (2016). Mental Health Disparities within the LGBT population: A comparison between transgender and nontransgender individuals. Transgender Health, 1(1), 12–20. https://doi.org/10.1089/trgh.2015.0001

- Aizenkot, D. (2021). The Predictability of Routine Activity Theory for Cyberbullying Victimization among Children and Youth: Risk and Protective factors. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 37(13–14), NP11857–NP11882. https://doi.org/10.1177/0886260521997433

- Navarro, J. N., & Jasinski, J. L. (2011). Going Cyber: Using routine activities theory to predict cyberbullying experiences. Sociological Spectrum, 32(1), 81–94. https://doi.org/10.1080/02732173.2012.628560